“Come you ladies and you gentlemen and listen to my song. I’ll sing it to you right, but you might think it’s wrong…”

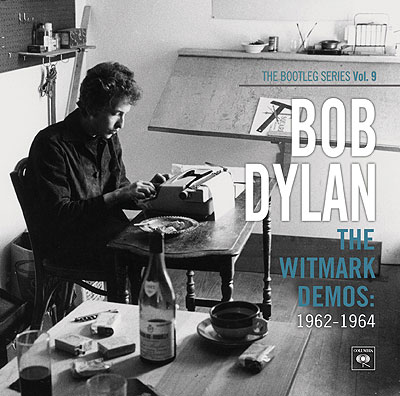

During the second coming of the personality profile assignment I was reminded by a classmate of a certain musical passion of mine: Bob Dylan. I’ve written about a number of other artists and albums (the number 4 to be exact), but not Dylan, and jeez louise that’s just not right. He is this blog’s namesake - as well as this man’s namesake - after all. He’s earned himself a little recognition. So, to right a wrong, here is a quick look at Dylan’s latest release, The Witmark Demos: 1962 – 1964.

The Witmark Demos are volume 9 in the ongoing Bob Dylan bootleg releases – a series of compilations which began in the early 90’s and have been neatly compiling Dylan’s outtakes and live performances. The album is comprised of 47 tracks and stretches over two discs.

The album is rough, sparse, and intimate, pulling you through your headphones or speakers and placing you in the room with Dylan. That is the album’s strongest trait, and its greatest allure.

When Dylan says “Jesus Christ, I can’t get it. I lost the verses,” at the end of the first track, “Man on the Street (Fragment),” it is as if the words are directed towards the listener – there is no response from anyone who was with Dylan, no acknowledgment. These simple mistakes and musings – although I’m sure they’ll become tiresome after multiple listens – provide Dylan with a vulnerability that is missing on a lot of his albums (besides, maybe, Another Side of Bob Dylan). The same can be said for the rhythmic slap of Dylan’s foot against the floor on the previously unreleased “Ballad for a Friend.” An honest sound that would most likely have been eliminated from a studio album.

The Witmark Demos contains 15 previously unreleased songs, the other 32 being alternate/early takes of songs that have appeared on Dylan’s albums or other volumes of the bootleg series. The new tracks are uniformly strong, with the somber “Guess I’m Doing Fine” being a standout. The alternate versions of classics, however, are revelatory. Hearing “Mr. Tambourine Man” slowed down to a dirge, accompanied by only a piano is something I could have lived without. The takes of “Tomorrow is a Long Time” and “Mama, You Been on My Mind,” on the other hand, glimmer with a stuffy sophistication.

Essentially, the album’s target market is Bob Dylan fans. If you’re familiar with these songs, the early versions are like watching God make Genesis and all that good stuff happen. If you’re not, then this might not be the best place to start. But whatever, hearing these songs now its easy to see why they found him some famous fans.

Listening recommendations: After: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are A-Changin’. Before: Finding a new musical deity.